[caption id="attachment_1048" align="alignleft" width="2487"]

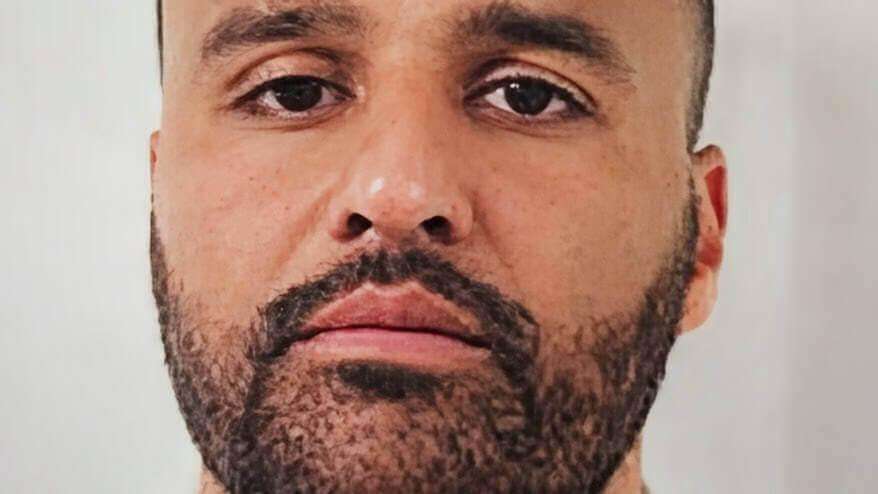

Rishi Sunak has his work cut out. Credit: Getty

Rishi Sunak has his work cut out. Credit: Getty[/caption]

For all the wrong reasons, Britain is once again at the top of the G7 league tables. According to recent statistics, the nation not only pays the highest interest rates on its national debt but also has some of the lowest labor productivity, which is noteworthy given that there are currently no standouts in the latter category.

British interest rates are higher in part because of the government's increased exposure to inflation-indexed interest rates and foreign investors, who possess a larger portion of the country's debt than in other G7 nations. Not only has this ensured that interest rates rise in line with inflation, but they also leave the Government dependent on the whims of strangers, as Mark Carney put it and as Liz Truss found to her (and millions of mortgage-holders’) sorrow.

However, the twin failings of high debt charges and low productivity are also probably related. An ageing population produces a rising dependency ratio, meaning that every working person must support a growing number of retirees. Unless a country supercharges its immigration policy, as Canada has done, it must increase what each worker produces just to be able to keep these people in the style to which they’ve grown accustomed. Britain has done neither. Yet both the Government and Opposition, which remain committed to the triple lock on pensions, are determined to maintain the living standards of pensioners.

Since workers can’t keep up with these demands, either taxes or borrowing must rise. At the moment, both are happening in Britain, with taxes rising by stealth as taxpayers are pushed into higher brackets (even though their real incomes might not have moved much). Either outcome alerts investors to the uninspiring long-term prospects of the economy, especially when the rise in borrowing is used to fund current rather than capital spending. In response, investors demand a higher risk premium on UK debt, gradually making the country look in debt markets like an emerging economy. This is the slow downward spiral in which Britain currently finds itself.

Assuming that inflation continues to fall, some of the pressure will ease in the short term. But this won’t solve the problem, merely giving the country a bit of breathing room to find a solution. The Government, whether this one or a future Labour ministry, will have to either find a way to raise labour productivity or make some tough choices — like ending the triple lock on pensions or raising headline taxes.

What’s more, raising labour productivity would itself likely involve tough choices. Over the last decade, one of the most lucrative possible investments was in real estate, beating stocks and savings accounts by some distance. Both the Bank of England and Government juiced property markets with a combination of easy money and demand-stimulating policies, such as Help to Buy and stamp duty cuts.

But — unlike factories or restaurants — once built, houses produce nothing. And because property owners prefer that new houses not be built, since that can inhibit the price of their own investment, governments have repeatedly succumbed to their demands, limiting housebuilding and further inflating this non-productive sector of the economy.

It’s widely accepted that Britain won’t raise its labour productivity very much until it raises its low rate of business investment. To do this would probably require it to reduce the returns on real estate. At the moment, nobody seems in a rush to do that.

Rishi Sunak has his work cut out. Credit: Getty[/caption]

For all the wrong reasons, Britain is once again at the top of the G7 league tables. According to recent statistics, the nation not only pays the highest interest rates on its national debt but also has some of the lowest labor productivity, which is noteworthy given that there are currently no standouts in the latter category.

British interest rates are higher in part because of the government's increased exposure to inflation-indexed interest rates and foreign investors, who possess a larger portion of the country's debt than in other G7 nations. Not only has this ensured that interest rates rise in line with inflation, but they also leave the Government dependent on the whims of strangers, as Mark Carney put it and as Liz Truss found to her (and millions of mortgage-holders’) sorrow.

However, the twin failings of high debt charges and low productivity are also probably related. An ageing population produces a rising dependency ratio, meaning that every working person must support a growing number of retirees. Unless a country supercharges its immigration policy, as Canada has done, it must increase what each worker produces just to be able to keep these people in the style to which they’ve grown accustomed. Britain has done neither. Yet both the Government and Opposition, which remain committed to the triple lock on pensions, are determined to maintain the living standards of pensioners.

Since workers can’t keep up with these demands, either taxes or borrowing must rise. At the moment, both are happening in Britain, with taxes rising by stealth as taxpayers are pushed into higher brackets (even though their real incomes might not have moved much). Either outcome alerts investors to the uninspiring long-term prospects of the economy, especially when the rise in borrowing is used to fund current rather than capital spending. In response, investors demand a higher risk premium on UK debt, gradually making the country look in debt markets like an emerging economy. This is the slow downward spiral in which Britain currently finds itself.

Assuming that inflation continues to fall, some of the pressure will ease in the short term. But this won’t solve the problem, merely giving the country a bit of breathing room to find a solution. The Government, whether this one or a future Labour ministry, will have to either find a way to raise labour productivity or make some tough choices — like ending the triple lock on pensions or raising headline taxes.

What’s more, raising labour productivity would itself likely involve tough choices. Over the last decade, one of the most lucrative possible investments was in real estate, beating stocks and savings accounts by some distance. Both the Bank of England and Government juiced property markets with a combination of easy money and demand-stimulating policies, such as Help to Buy and stamp duty cuts.

But — unlike factories or restaurants — once built, houses produce nothing. And because property owners prefer that new houses not be built, since that can inhibit the price of their own investment, governments have repeatedly succumbed to their demands, limiting housebuilding and further inflating this non-productive sector of the economy.

It’s widely accepted that Britain won’t raise its labour productivity very much until it raises its low rate of business investment. To do this would probably require it to reduce the returns on real estate. At the moment, nobody seems in a rush to do that.

Rishi Sunak has his work cut out. Credit: Getty[/caption]

For all the wrong reasons, Britain is once again at the top of the G7 league tables. According to recent statistics, the nation not only pays the highest interest rates on its national debt but also has some of the lowest labor productivity, which is noteworthy given that there are currently no standouts in the latter category.

British interest rates are higher in part because of the government's increased exposure to inflation-indexed interest rates and foreign investors, who possess a larger portion of the country's debt than in other G7 nations. Not only has this ensured that interest rates rise in line with inflation, but they also leave the Government dependent on the whims of strangers, as Mark Carney put it and as Liz Truss found to her (and millions of mortgage-holders’) sorrow.

However, the twin failings of high debt charges and low productivity are also probably related. An ageing population produces a rising dependency ratio, meaning that every working person must support a growing number of retirees. Unless a country supercharges its immigration policy, as Canada has done, it must increase what each worker produces just to be able to keep these people in the style to which they’ve grown accustomed. Britain has done neither. Yet both the Government and Opposition, which remain committed to the triple lock on pensions, are determined to maintain the living standards of pensioners.

Since workers can’t keep up with these demands, either taxes or borrowing must rise. At the moment, both are happening in Britain, with taxes rising by stealth as taxpayers are pushed into higher brackets (even though their real incomes might not have moved much). Either outcome alerts investors to the uninspiring long-term prospects of the economy, especially when the rise in borrowing is used to fund current rather than capital spending. In response, investors demand a higher risk premium on UK debt, gradually making the country look in debt markets like an emerging economy. This is the slow downward spiral in which Britain currently finds itself.

Assuming that inflation continues to fall, some of the pressure will ease in the short term. But this won’t solve the problem, merely giving the country a bit of breathing room to find a solution. The Government, whether this one or a future Labour ministry, will have to either find a way to raise labour productivity or make some tough choices — like ending the triple lock on pensions or raising headline taxes.

What’s more, raising labour productivity would itself likely involve tough choices. Over the last decade, one of the most lucrative possible investments was in real estate, beating stocks and savings accounts by some distance. Both the Bank of England and Government juiced property markets with a combination of easy money and demand-stimulating policies, such as Help to Buy and stamp duty cuts.

But — unlike factories or restaurants — once built, houses produce nothing. And because property owners prefer that new houses not be built, since that can inhibit the price of their own investment, governments have repeatedly succumbed to their demands, limiting housebuilding and further inflating this non-productive sector of the economy.

It’s widely accepted that Britain won’t raise its labour productivity very much until it raises its low rate of business investment. To do this would probably require it to reduce the returns on real estate. At the moment, nobody seems in a rush to do that.

.svg)