A dilapidated old caravan belonging to Charlie Holt strikes an odd note on a white stuccoed terraced street in a posh part of London. "I bought it for £250 from a guy around the corner," he claims. Angel, his dog, is standing calmly by his side.

For over a month now, Holt, 62, has been residing in the dilapidated caravan. He claims that while a few neighbours on the Pimlico street where it is stationed have voiced their disapproval, most don't appear to mind his presence. "I'm not housed," he says. "You have two weeks from now to depart, the council said. They haven't returned since then.

Holt ended himself here because his privately rented Blackpool flat became dilapidated. He talks of serving as a Fusilier in the Army during the first part of the 1980s and claims to have worked as a mechanic and handyman for the most of his post-service career. Due to a back issue that he believes resulted from his prior work, he can no longer work. Still several years shy of retirement age, he finds himself dependent on Universal Credit. At the end of each day, he helps out at a local cafe, closing up, and is rewarded with meals.

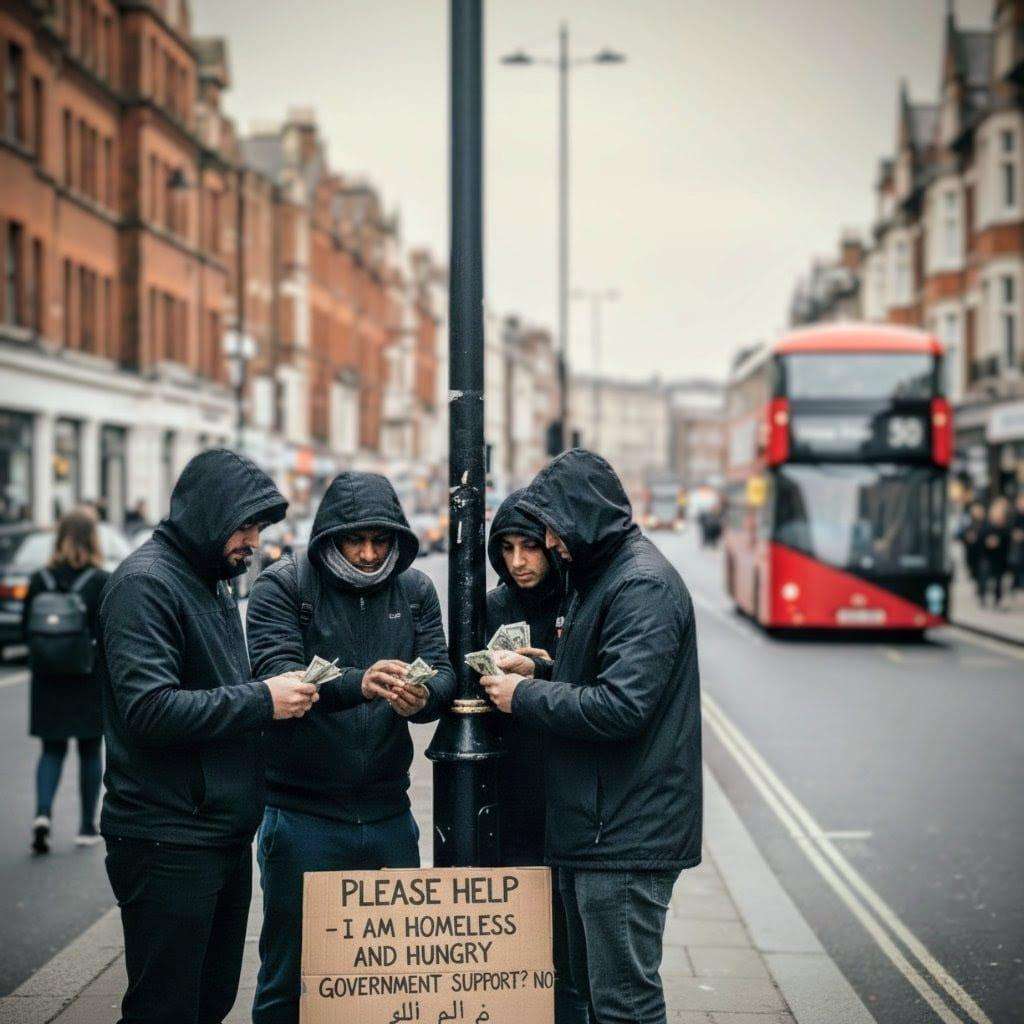

In his Union flag hoodie and jeans, Holt is one of hundreds of homeless people in the borough of Westminster and one of thousands across the capital. In the year to March, the number of people sleeping rough in London reached a record high of 11,993, according to the Combined Homelessness and Information Network.

Westminster has long been the epicentre of Britain’s homelessness problem, recording the highest number of rough sleepers throughout the past 14 years. In an area known for smart restaurants, multimillion-pound addresses and the infrastructure of government, the inequality is stark.

Half a mile down the road from Holt’s shabby caravan, the trendy food court Market Halls opened in 2018, opposite London’s Victoria railway station. Come lunchtime, the place is filled with well-heeled office workers wearing their lanyards and eating global cuisine off canteen-style trays. A year earlier, Nova opened nearby: a sleek glass and chrome development on the other side of Victoria Street, with a line-up of atmospherically-lit restaurants. A donut van sells its wares on the concourse here for up to £6 a pop.

Yet just yards away, the other face of this teeming part of the capital can be seen. Along a strip of pavement near a branch of Pret A Manger, rough sleepers and beggars huddle in sleeping bags, asking passers-by for spare change. Emaciated drug users hurtle past, bellowing at each other. A woman pushes her belongings in a wheelie bag.

“There are way more rough sleepers now,” says Cyrin Senez, who is rolling out pastry in Gigi, a smart French patisserie on the street. “It’s so sad,” agrees his co-worker Fanny Prade. “The number of homeless people is, like, double [what it was]. I think it’s the same thing everywhere.”

Figures from the Greater London Authority last summer showed rough sleeping was soaring in London, with over 1,700 more people on the streets than the previous year – a 21 per cent rise. In 2022-23, more than 10,053 people were sleeping rough in London.

In Westminster, one of the capital’s most affluent boroughs, the Labour-run local authority has been keen to blame the spike in rough sleeping on the previous Conservative government’s policy of trying to move asylum seekers out of hotels and hostels within 28 days. But Naushabah Khan, policy director at homelessness charity St Mungo’s, says a variety of factors are at play, including asylum policy.

“On a wider level, the cost of living crisis has had a significant impact, and rising rents,” she says.

Elsewhere in the borough, on a strip of land in the middle of Mayfair’s Park Lane, in the shadow of the five-star hotels and gleaming car showrooms, a tent city of rough sleepers was established some years ago. The mostly Romanian occupants of the most recent iteration of the encampment reflect the fact that more than half of London’s rough sleepers come from overseas.

But the problem, of course, extends far beyond London. Annual figures released by the government in February showed the number of people in England estimated to be sleeping rough on a single night in autumn 2023 was 3,898 – a 27 per cent rise on the number from 2022 and an increase of 120 per cent since 2010.

The reasons include a range of interconnecting personal and structural factors, from mental health issues, substance dependence, relationship breakdown and poverty to a lack of social rented housing and rising living costs. UK nationals remained the largest proportion of people (62 per cent) found to be sleeping rough around the country.

Among them are those like Holt, whose precarious economic situation tipped him from poor-quality housing into homelessness. He is currently waiting to be housed by the council. Originally from Bangor in North Wales, the father-of-two says he has lived all over the UK since leaving home at 15.

“Back in Birmingham in the Seventies and Eighties, they were the best days of my life,” he recalls wistfully. The words “rock and roll” are tattooed on his right hand.

This isn’t the first time he has been homeless: his initial spell was two years long, starting in 2016. Before he obtained the caravan this autumn, he spent five months living on the streets near Buckingham Palace. The dilapidated state of the £500-a-month home he previously occupied, in an old Victorian public building converted into flats, was what drove him onto the streets, he says.

“I realised my place in Blackpool was starting to crumble. Water was coming through the floor. All the brickwork was crumbling. It was rotten.”

Inside his new temporary home, he has electricity, a bed to sleep in – and the ashes of another pet dog, named Storm, who recently died and now resides in a cardboard urn. Holt’s grown-up children live elsewhere. He hopes that by next month, the council will be able to offer him proper accommodation. In the meantime, he says he doesn’t mind living in the caravan too much. “It’s cheaper [than renting],” says Holt. “All you’ve got to pay for is your groceries.”

He's got plenty of friends in London, Birmingham, and Blackpool who are in similar circumstances. Politicians make promises to assist people, but they don't always follow through. By 2024, the Conservatives wanted to put a stop to rough sleeping. Labour deputy prime minister Angela Rayner has since talked of getting “back on track towards ending homelessness for good”, with a plan to build additional social housing, among other commitments. Holt and countless others will be in wait.

.svg)