The early onset and consequences of Type 2 diabetes in British Asians are caused by genetic factors, according to a recent study.

A lower reaction to some drugs, an earlier requirement for insulin treatment, and a faster onset of health issues are also caused by these hereditary variables.

The study's findings underscore the importance of comprehending the ways in which genetic diversity among various demographic groups might impact disease onset, responsiveness to treatment, and progression.

Researchers at Queen Mary examined information from the Genes & Health cohort, a community-based study of over 60,000 volunteers who are British-Pakistani and British-Bangladeshi who have donated their DNA for genetic research.

Researchers linked genetic information to NHS health records in 9,771 Genes & Health volunteers with a Type 2 diabetes diagnosis and 34,073 diabetes-free controls to understand why British Asians develop the chronic disease at a younger age and often with normal body mass index, compared to white Europeans.

It found that the younger age of onset in South Asians is linked to genetic signatures that lead to lower insulin production and unfavourable patterns of body fat distribution and obesity.

The most significant genetic signature is a reduced ability of pancreatic beta cells to produce insulin.

It also increases the risk of gestational diabetes and the progression of gestational diabetes to Type 2 diabetes after pregnancy.

The identified genetic signatures provide vital clues about how different people may respond to Type 2 diabetes treatment.

The study revealed a high genetic risk group, who were found to develop Type 2 diabetes an average of eight years earlier and at lower body mass index.

Over time, they were more likely to need insulin treatment and were at higher risk for diabetes complications such as eye and kidney disease.

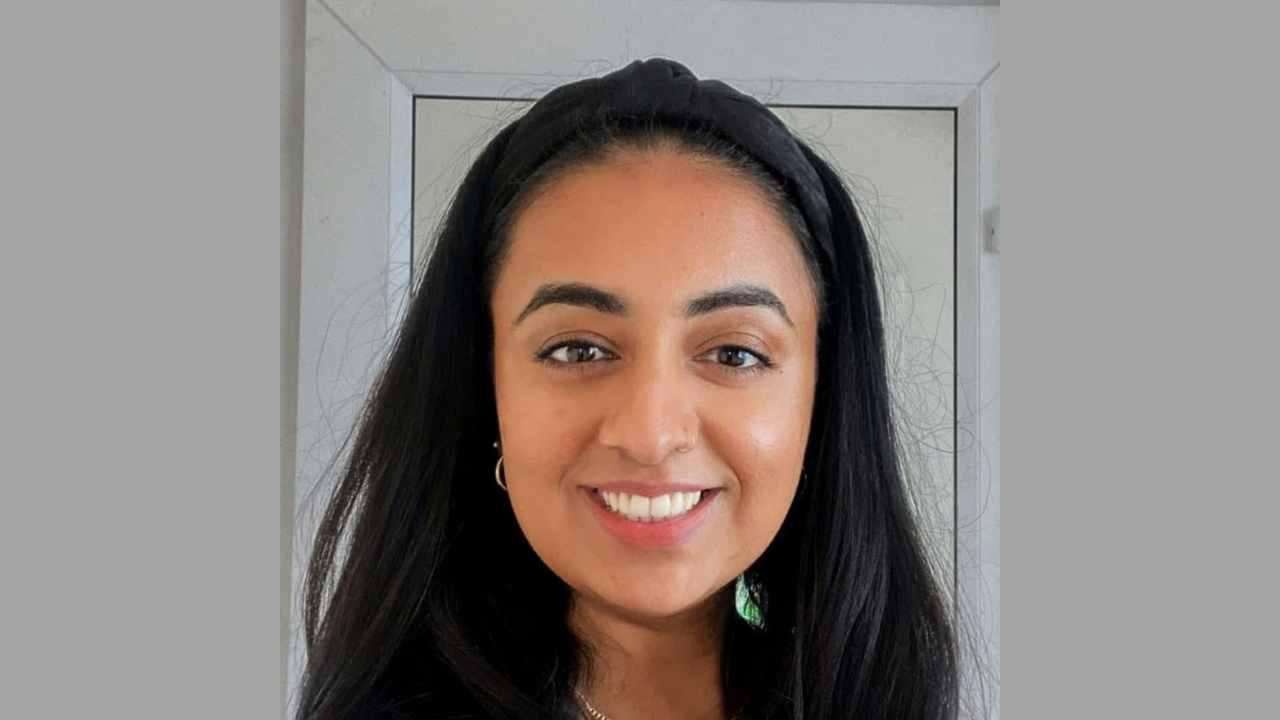

Sarah Finer, Clinical Professor in Diabetes from the Wolfson Institute of Population Health and Diabetes Consultant at Barts Health NHS Trust, said:

“Thanks to the participation of so many British Bangladeshi and British Pakistani volunteers in Genes & Health, we have found important clues as to why Type 2 diabetes may develop in young, slim individuals.

“This work also tells us how important it is to move away from a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to managing Type 2 diabetes.”

“We hope that this will allow us to find ways to offer more precise treatments that treat the condition more effectively and reduces the development of diabetes complications.”

Dr Moneeza K Siddiqui, Lecturer in Genetic Epidemiology from the Clinical Effectiveness Group in the Wolfson Institute of Population Health, said:

“We don’t yet know whether genetic tools will be needed to deliver precision diabetes medicine in South Asian populations, or whether we can better and more widely use existing laboratory tests such as C-peptide which can be measured in a simple blood test.

“Genes & Health will contribute to future efforts to ensure that precision medicine approaches are developed and bring real benefits to South Asian communities living with, and at risk of Type 2 diabetes.”

.svg)