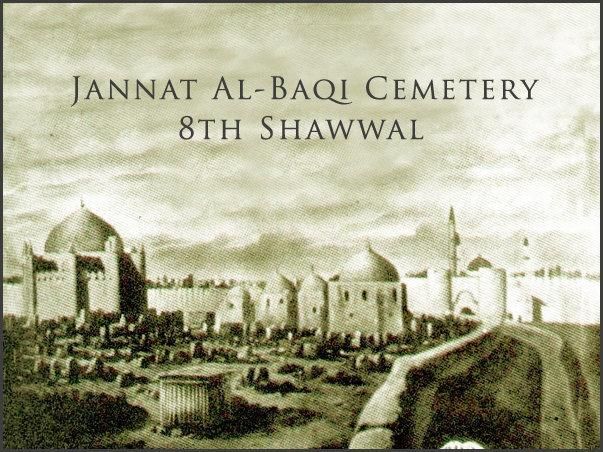

The Tragedy of Jannatul-Baqi’s Demolition – 8 Shawwal, 1345 AH (April 21, 1925)

The demolition of Jannatul-Baqi in Madinah by the Al-e-Saud regime on 8 Shawwal, 1345 AH (April 21, 1925) stands as a profound tragedy in Islamic history. Though a cemetery in appearance, Jannatul-Baqi holds immense significance for Muslims worldwide. It is the resting place of revered figures, including the Holy Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) close companions and his infallible progeny: Imam Hasan ibn Ali (2nd Imam), Imam Ali ibn al-Husayn (4th Imam), Imam Muhammad ibn Ali (5th Imam), and Imam Ja’far ibn Muhammad (6th Imam), peace be upon them all.

That same year, the graves of the Prophet’s mother, wife, grandfather, and other ancestors in Jannat al-Mualla, Makkah, were also demolished by order of King Saud bin Abdul Aziz.

Many scholars believe these acts were part of a broader plot, disguised under the banner of Tawheed, to erase Islamic heritage and disconnect Muslims from their spiritual and historical legacy. Some view this as a Zionist-backed conspiracy aimed at weakening the foundations of Islamic unity and reverence.

This agenda continues today through extremist groups like ISIL (Daesh) in Iraq and Syria, who have destroyed sacred shrines, including those of Prophets Yunus and Shish (peace be upon them), and companions of the Prophet (PBUH) such as Ammar bin Yasir and Hujr ibn Adi. ISIL, seen as a proxy for Saudi interests and Western powers, has even targeted the shrine of Hazrat Zainab (AS), the Prophet’s granddaughter and sister of Imam Hussain (AS).

The Origins of Al-Baqi

The word Al-Baqi literally means a garden with trees. Due to its sacred nature, it is also called Jannat al-Baqi, as it houses the graves of many of the Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) family members and companions.

The first person to be buried in Al-Baqi was Uthman ibn Mazh’un, who passed away on the 3rd of Sha’ban in the 3rd year after Hijrah. The Prophet (PBUH) personally chose the site, removed some trees, and placed two stones to mark the grave. Later, the Prophet’s young son Ibrahim, who died in infancy, was also laid to rest there—an event that caused the Prophet deep sorrow.

Following these burials, the people of Madinah began using the area as a cemetery. The Prophet (PBUH) would often offer greetings to those buried there, saying: "Peace be upon you, O abode of the faithful! God willing, we shall soon join you. O Allah, forgive the people of Al-Baqi."

Over time, Al-Baqi expanded significantly. It became the final resting place of nearly seven thousand companions, along with members of the Prophet’s family (Ahlul Bayt), including Imam Hasan ibn Ali (AS), Imam Ali ibn al-Husayn (AS), Imam Muhammad al-Baqir (AS), and Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq (AS). Other relatives buried there include his aunts Safiya and Atika, and Fatima bint Asad, the mother of Imam Ali (AS).

The third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan, was initially buried outside the cemetery, but later expansions brought his grave within its bounds. Renowned Islamic scholars, such as Malik ibn Anas and others, were also buried in Al-Baqi, making it a site of immense historical and religious importance for Muslims worldwide.

Al-Baqi Through the Eyes of Historians

The renowned traveler Umar ibn Jubair documented his observations of Al-Baqi during his visit to Madinah. He noted that Al-Baqi lies to the east of the city and is entered through a gate known as Bab al-Baqi. Upon entering, the first grave on the left belongs to Safiya, the Prophet’s aunt, followed by the grave of Malik ibn Anas, the famous Imam of Madinah, which had a small dome over it.

Nearby stood the grave of the Prophet’s son, Ibrahim, marked with a white dome. To the right of it was the grave of Abdul-Rahman, son of Umar ibn al-Khattab—commonly known as Abu Shahma—who died after enduring punishment from his father. Across from these graves are those of Aqeel ibn Abi Talib and Abdullah ibn Ja’far al-Tayyar.

There was also a small shrine containing the graves of the Prophet’s wives, followed by another shrine marking the resting place of Abbas ibn Abdul Muttalib. Close to the entrance, on the right side, stood the grave of Imam Hasan ibn Ali (AS), covered by a raised dome. His head was positioned near the feet of Abbas, and both tombs were elevated, decorated with yellow panels and star-shaped metal studs. The grave of Ibrahim, the Prophet’s son, was similarly adorned.

Behind Abbas’s shrine stood a house known as Bayt al-Ahzaan—the House of Sorrows—associated with Fatima (SA), the Prophet’s daughter, where she would go to mourn her father’s death. At the far end of Al-Baqi was the grave of Caliph Uthman, also covered by a small dome, and nearby was the grave of Fatima bint Asad, the mother of Imam Ali (AS).

About 150 years later, the famed traveler Ibn Battuta visited Al-Baqi and described it in much the same way, adding that it contained the graves of many Muhajirin and Ansar, along with other companions of the Prophet, though many of their names had been lost over time.

For centuries, Al-Baqi remained a revered site, maintained and renovated as needed. However, this changed in the early 19th century with the rise of the Wahhabi movement. They destroyed many of the tombs and showed open disregard for the sacredness of the graves of the Prophet’s family and companions. Those who opposed their views were declared unbelievers and often met with violent persecution.

The First Demolition of Al-Baqi

The Wahhabi ideology considered visiting the graves of prophets, imams, and saints as a form of shirk (idolatry) and contrary to Islamic teachings. Those who rejected their beliefs were often killed, and their possessions seized. From their early campaigns in Iraq to the present day, Wahhabis—alongside some Gulf rulers—have carried out violent acts against Muslims who opposed them.

In contrast, the broader Muslim world has always regarded these graves and shrines with deep respect. Proof of this reverence lies in the fact that Caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar requested to be buried near the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH).

Between 1205 AH and 1217 AH, the Wahhabis repeatedly tried to invade the Hijaz region but failed. Their breakthrough came in 1217 AH when they captured Taif, brutally massacring many innocent Muslims. The following year, they entered Makkah and destroyed various sacred sites, including the dome that once covered the Zamzam well.

By 1221 AH, they advanced into Madinah and began their campaign of destruction, targeting Al-Baqi and several mosques. They even considered demolishing the Prophet’s tomb but ultimately abandoned the idea. In the years that followed, Muslims from regions like Iraq, Syria, and Egypt were barred from performing Hajj unless they accepted Wahhabi doctrine. Those who refused were declared non-Muslims and denied entry to the holy sites.

The destruction of Al-Baqi left no visible signs of graves or tombs. Still unsatisfied, the Wahhabi leadership coerced the custodians of the Prophet’s shrine to reveal hidden treasures, which were then looted for their own use.

Widespread fear and persecution forced many Muslims to flee Makkah and Madinah. Outrage over these atrocities spread across the Muslim world, with calls for the Ottoman Caliphate to step in and protect the sanctity of Islamic heritage.

In response, Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt launched a military campaign and, with help from local tribes, drove the Al-Saud forces out of the Hijaz, restoring peace to the holy cities. This victory was celebrated joyfully across the Muslim world—festivities in Cairo alone lasted five days. The return of religious freedom and access to the shrines brought immense relief to Muslims everywhere.

In 1818 AD, Ottoman Caliph Abdul Majid, followed by Caliphs Abdul Hamid and Mohammed, led efforts to rebuild and restore Islamic sites. Further renovations were carried out in 1848 and 1860, funded by donations—many of which came from offerings at the Prophet’s tomb—totaling nearly £700,000.

The Second Destruction by the Wahhabis

During the era of the Ottoman Empire, Madinah and Makkah were enriched with magnificent religious structures known for their beauty and architectural significance. In 1853 AD, British traveler Richard Burton, disguised as a Muslim named Abdullah, noted that Madinah housed 55 mosques and sacred sites. Another Western visitor, who came between 1877–1878 AD, described the city as charming and reminiscent of Istanbul, with its white walls, golden minarets, and lush green surroundings.

However, in 1924 AD, the Wahhabis launched a second brutal invasion of the Hijaz. Their advance brought devastation—massacres filled the streets, homes were demolished, and even women and children were not spared. Awn bin Hashim, the Sharif of Makkah, described the horror: “Before me stretched a valley covered with corpses, dried blood staining everything. Almost every tree had one or two bodies lying beneath it.”

By 1925, Madinah had surrendered. The Wahhabis destroyed nearly all signs of Islamic heritage, sparing only the Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) shrine. One Wahhabi scholar, Ibn Jabhan, stated: “We know the tomb over the Prophet’s grave contradicts our beliefs, and placing his grave in a mosque is a grave sin.”

The tombs of Hamza and other martyrs at Uhud were also destroyed. The Prophet’s mosque itself was bombarded. Though Ibn Saud initially promised its restoration in response to public outrage, he never fulfilled the commitment. He had also pledged to establish a multinational Islamic government in Hijaz—this too was abandoned.

That same year, in 1925 AD, Jannat al-Mu'alla, the revered cemetery in Makkah, was leveled. Even the house where the Prophet (PBUH) was born was demolished. Since then, this day is observed as a day of grief by Muslims across the world.

It is ironic that while Wahhabis deem the preservation of holy tombs and sacred sites as forbidden, they continue to guard and maintain the graves of Saudi kings at great financial cost.

Protests from Indian Muslims

In 1926, Muslims across India and the world organized protest gatherings in response to the Wahhabi-led destruction of Islamic heritage. Various resolutions were adopted, condemning the acts committed in the Hijaz. A formal declaration was issued listing several major concerns:

1. The desecration of sacred sites, including the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), the graves of Banu Hashim in Makkah, and those in Jannat al-Baqi in Madinah, as well as the Wahhabis’ prohibition against reciting Ziyarah or Surah Al-Fatiha at these graves.

2. The destruction of mosques such as Masjid Hamza and Masjid Abu Rasheed, along with the tombs of revered Imams and companions of the Prophet.

3. Interference with the proper observance of Hajj rituals.

4. Forcing Muslims to abandon their traditional practices and follow Wahhabi interpretations.

5. Massacres of Sayyids in regions like Taif, Madinah, Ahsa, and Qatif.

6. The destruction of the Imams’ graves at Al-Baqi, which caused profound sorrow and anger among Shia Muslims.

Protests from Other Nations

Similar reactions were echoed in countries such as Iran, Iraq, Egypt, Indonesia, and Turkey. Muslims in these nations also denounced the Saudi Wahhabis for their violent actions. Scholars from various parts of the world authored pamphlets and books to raise awareness, arguing that the events in Hijaz were part of a broader conspiracy—one allegedly orchestrated by Jews to weaken Islam under the guise of Tawheed (monotheism). Their goal, as explained by these scholars, was to erase Islamic heritage and strip future generations of their connection to the religion’s sacred history.

.svg)