The UK labour market is celebrating significant strides in pay equity, with the national gender pay gap for full-time employees falling to a record low of 6.9% in April 2025. This, coupled with the proportion of workers in low-paid jobs hitting an unprecedented low of 2.5%, marks genuine progress in reducing overall pay inequality. However, this success is overshadowed by alarming data revealing a persistent, deep-seated economic disadvantage for the Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and wider Muslim and South Asian communities.

While median weekly earnings rose by 5.3% to £766.60, the benefits of this economic growth are not being equally distributed, underscoring a two-tier pay reality in the UK.

The Structural Roots of the Disparity

ONS and comprehensive labour market analysis consistently show that Bangladeshi and Pakistani workers, as key sub-groups of the UK's South Asian and Muslim populations, endure some of the lowest median earnings and highest rates of poverty. The primary reasons for this profound lag are structural, systemic, and cumulative, creating a "double" or even "triple penalty" of disadvantage.

Occupational Segregation and Low Pay

The most significant factor is the severe concentration of Bangladeshi and Pakistani workers in low-paid occupations. These groups are statistically far more likely to be employed in lower-skilled and service-sector roles, and consequently are significantly more likely than any other ethnic group to be paid below the real Living Wage. This occupational segregation acts as a persistent barrier to upward mobility. Furthermore, even when comparing like-for-like roles, studies indicate that a pay gap persists, suggesting a fundamental lack of progression and a penalty for being in these groups.

The Compounded Penalty for Women

The crisis is particularly acute for women of Bangladeshi and Pakistani heritage, who face the combined effect of gender, race, and, often, religious bias. Research has highlighted "shocking pay gaps" for these women compared to men in their own communities (for example, a 60% gap for Pakistani women and a 50\% gap for Bangladeshi women in London), a disparity far exceeding the national gender pay gap.

This inequality is not merely a result of individual "cultural choices," as is often stereotypically assumed. Instead, systemic barriers are primarily responsible. Pakistani and Bangladeshi women face higher unemployment rates and economic inactivity due to:

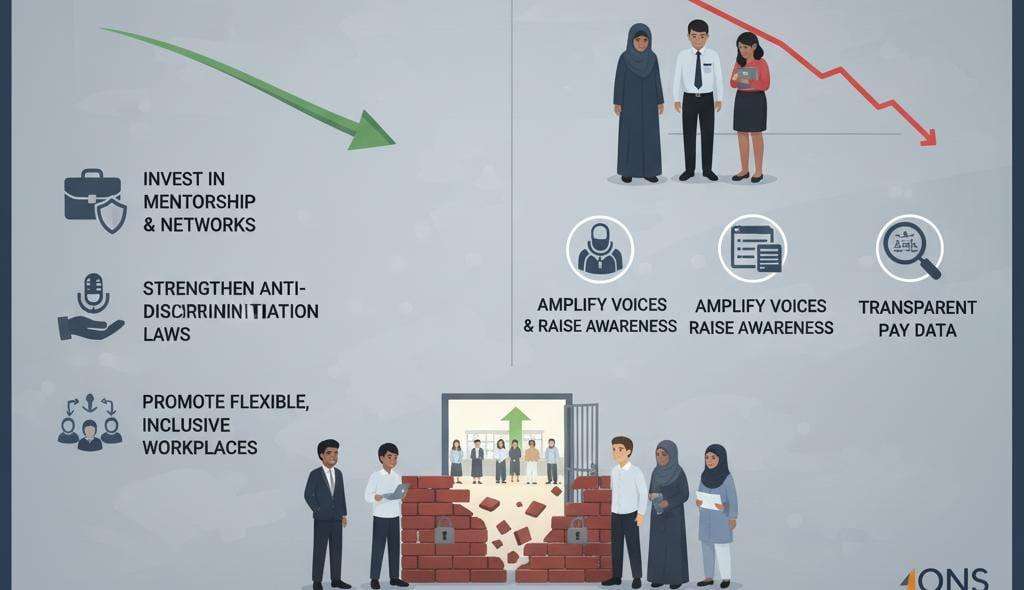

- Lack of Resources and Networks: Limited access to professional networks, mentorship, and financial resources for training.

- Systemic Discrimination: Direct racism in recruitment, often involving discrimination based on names or the wearing of the hijab, and being routinely passed over for promotions in favour of less experienced White colleagues.

- Inflexible Workplaces: Lack of culturally appropriate, affordable childcare and rigid workplace practices make it difficult to balance work with family responsibilities.

The Migration and Generational Divide

The level of pay disadvantage is strongly linked to migration status. Male Bangladeshi immigrants, for instance, have historically faced the largest pay gaps, in some cases earning nearly 50\% less than their White British male counterparts. This is driven by challenges specific to new arrivals, including:

- Language and Qualifications: Difficulties with English language proficiency and the non-recognition of overseas qualifications, which forces skilled workers into roles beneath their capabilities.

- Visa Restrictions: Uncertainty and limitations imposed by visa rules often restrict the employment options and progression routes for recent migrants.

While British-born workers in these communities face smaller gaps, they are still present, proving that the disadvantage is not solely a first-generation issue. The overall result is a disproportionately high percentage of Bangladeshi and Pakistani households in the lowest income quintiles, cementing a cycle of economic hardship.

TUC General Secretary Paul Nowak welcomed the progress on the national gender gap but stressed that, at the current rate, women would wait 31 years for pay parity. For Muslim and South Asian women facing a "triple penalty," the wait for true equality will be even longer unless decisive, targeted action is taken to dismantle the structural barriers identified in the ONS data and associated reports.

.svg)