International students and migrants arriving in the United Kingdom face the most significant tightening of settlement rights in a generation, as the Labour government moves to close what it describes as a loophole of "visa abuse" within the higher education sector. Following a sharp rise in graduates claiming asylum rather than returning home, ministers have confirmed plans to double the time required to gain permanent residency.

Under the stringent new proposals, the qualifying period for Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR) will be extended from five years to ten years. In some cases, migrants could be forced to wait up to 20 years before they can settle permanently in Britain. The retrospective measures are set to impact an estimated 2.6 million people who have arrived in the country since 2021, signaling a fundamental shift toward a "contribution-based" immigration system.

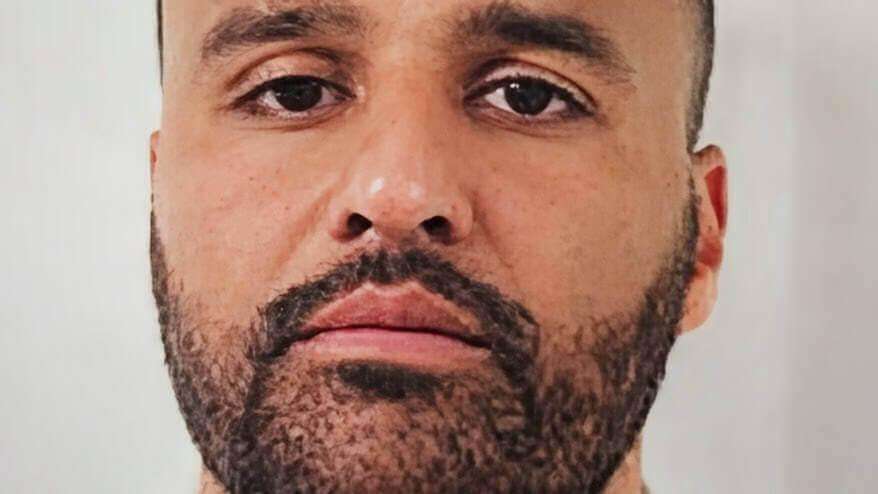

The overhaul comes amid growing government alarm regarding the integrity of the student visa route. Speaking during a diplomatic visit to Chennai, India, the UK’s Indo-Pacific Minister Seema Malhotra defended the hardline reforms as a necessary step to restore public confidence in border control. She cited "very strong" evidence that the student visa system is being exploited as a backdoor to asylum.

Home Office figures reveal a startling trend that has accelerated legislative action. Last year alone, approximately 16,000 international students applied for asylum in the UK after completing their courses. The surge has continued unabated, with a further 14,800 students seeking asylum in the first half of 2025. Minister Malhotra described this pattern as a clear undermining of legal migration routes, where individuals arrive legitimately but seek to overstay through asylum claims once their visas expire.

Malhotra emphasized that the reforms bring the UK in line with international standards, aiming to filter out those abusing the system while still welcoming genuine talent. She argued that seeing such high levels of abuse erodes the fairness and control that the British public expects from its government. Consequently, future settlement and long-term residency will depend heavily on an individual's sustained economic contribution rather than simply the length of time they have resided in the UK.

The clampdown has already begun to impact the demographic makeup of British universities. India, which remains the top source of foreign students accounting for 25 percent of arrivals, has seen demand cool significantly. Enrollment numbers from India have fallen by 11 percent compared to last year as the tougher immigration rhetoric and rules begin to bite. This decline has triggered anxiety among UK universities, many of which are already grappling with severe financial strain and rely heavily on the higher fees paid by international students.

Despite the cooling numbers, the government insists it is not closing the door to genuine Indian students or professionals. Malhotra highlighted the recently concluded Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the UK and India as evidence of continued partnership. The deal, signed in July, includes provisions for nine UK universities to establish campuses in India, with Liverpool University set to open a facility in Bengaluru in 2026. The government argues this allows for educational exchange without necessitating mass migration that strains public services.

However, the intersection of trade ambitions and migration control remains a point of friction. During his October visit to India, Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer remained firm that visa rules would not be relaxed simply to secure trade concessions, despite Delhi’s longstanding request for easier mobility for its citizens. The British government maintains that while nearly half a million visas were granted to Indian nationals last year across work and study categories, the path to remaining in the UK permanently must be harder to access.

The proposals have drawn criticism from some quarters within the Labour Party and the House of Lords, as well as industry bodies concerned about the wider economic fallout. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) has issued a stark warning that the extended settlement timelines could spark an exodus of healthcare professionals. An RCN survey suggests up to 50,000 nurses could leave the UK if the pathway to settlement becomes too difficult, a potential blow to the NHS which currently relies on an internationally educated workforce comprising 25 percent of its total nursing staff.

As the consultation period for these reforms concludes, the message from the Home Office is resolute. The era of the five-year fast track to settlement is effectively over for students and most migrants, replaced by a decade-long proving period designed to weed out abuse and ensure only those deeply committed to the UK’s economy remain.

.jpg)

.svg)

.jpg)