The promise of the British property dream is collapsing, but a damning new analysis reveals that the wreckage is not falling evenly. While the national conversation fixates on high interest rates and the struggles of 'Generation Rent,' a ground-breaking study led by the University of Stirling has exposed a more insidious driver of the housing crisis: deep-rooted structural inequality that is systematically locking British Bangladeshi families out of home ownership.

The research, funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in collaboration with Sheffield Hallam University, indicates that the decline in UK home ownership is not merely an economic issue but a racial one. However, a deeper dive into the data uncovers a specific, often overlooked crisis facing the British Bangladeshi community—a demographic facing a "double penalty" of location and systemic exclusion.

The 46 Percent Reality

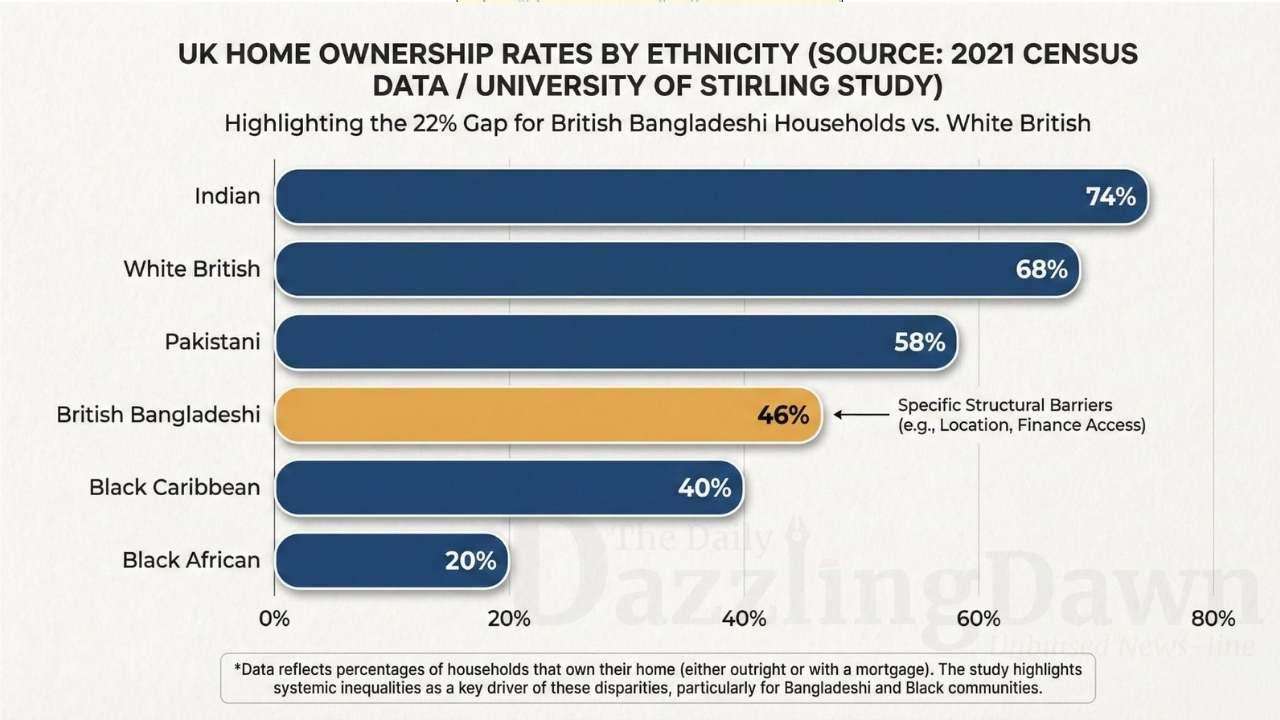

For decades, the "BAME" label has obscured distinct realities within ethnic minority groups. The new findings shatter this monolith, highlighting a staggering disparity. While 68 per cent of White British households and a thriving 74 per cent of Indian households have secured their footing on the property ladder, British Bangladeshi home ownership stands at a precarious 46 per cent.

This places the community 22 percentage points behind their White British counterparts and significantly lower than Pakistani households, who sit at 58 per cent. This specific disparity between Bangladeshi and Pakistani communities—often grouped together in policy discussions—points to unique structural barriers. The analysis suggests that geography plays a cruel role; a significant portion of the British Bangladeshi community is concentrated in Inner London boroughs like Tower Hamlets, where property values have decoupled from average earnings far more violently than in the Midlands or the North, where other diasporas are more heavily represented.

Beyond Prices: The Systemic Blockade

Dr Regina Serpa of the University of Stirling’s Faculty of Social Sciences emphasizes that the "unable to buy" narrative is insufficient. The study highlights that British Bangladeshi families are not just priced out; they are effectively shut out by institutions. The research points to a significant gap in access to credit and mortgage finance.

For many in the Bangladeshi community, the standard mortgage market is a closed door. This is exacerbated by a lack of competitive Sharia-compliant financial products, which are often more expensive than standard mortgages, creating a "faith penalty" for Muslim aspiring buyers. Furthermore, the prevalence of gig-economy work or multi-generational household incomes within the community is frequently penalized by rigid algorithmic credit scoring used by major high street lenders.

The Broken Promise of 'Right to Buy'

The report offers a scathing retrospective on the "Right to Buy" policy, introduced in 1980, which is often heralded as the democratisation of British property ownership. For British Bangladeshis, this policy served as a trap rather than a ladder.

The analysis details how the policy extended risk rather than wealth to low-income ethnic minority households. Many Bangladeshi families, historically housed in high-density, poor-quality inner-city council estates, found that purchasing these homes did not yield the asset appreciation seen in suburban semi-detached houses. Instead, they were often saddled with high-value but difficult-to-maintain properties in areas that did not benefit from the wider property boom in the same way, or were hit with crippling leasehold service charges that eroded their financial stability.

The Overcrowding Crisis

The implications of these statistics extend far beyond the balance sheet. The inability to buy has forced a disproportionate number of British Bangladeshi families into the private rental sector, where security of tenure is low and costs are exorbitant. This has directly fuelled an overcrowding crisis.

Updated data correlates the low 46 per cent ownership rate with some of the highest rates of household overcrowding in the UK. Unlike the "failure to launch" narrative applied to white millennials living with parents, multi-generational living in Bangladeshi households is often a necessity driven by housing exclusion. The study suggests that without targeted intervention that addresses race-specific barriers—rather than just general housing supply—these inequalities will entrench themselves for another generation, widening the wealth gap and damaging social mobility permanently.

Dr Serpa’s conclusion is a stark warning to policymakers: unless the government addresses the specific institutional discrimination facing groups like the British Bangladeshi community, the UK housing market will remain a vehicle for inequality rather than a foundation for stability.

.svg)