The architectural landscape of the United Kingdom is undergoing a quiet but profound transformation that has left hundreds of Grade-II listed buildings in a state of "protected decay." As traditional congregations dwindle, the push to repurpose these empty shells into vibrant Muslim community centers is hitting a wall of bureaucratic resistance. While local authorities cite "heritage preservation" and "traffic concerns," a deeper analysis of recent planning data reveals a growing disconnect between the preservation of stone and the needs of a modern, multi-faith society, Daily Dazzling Dawn realized.

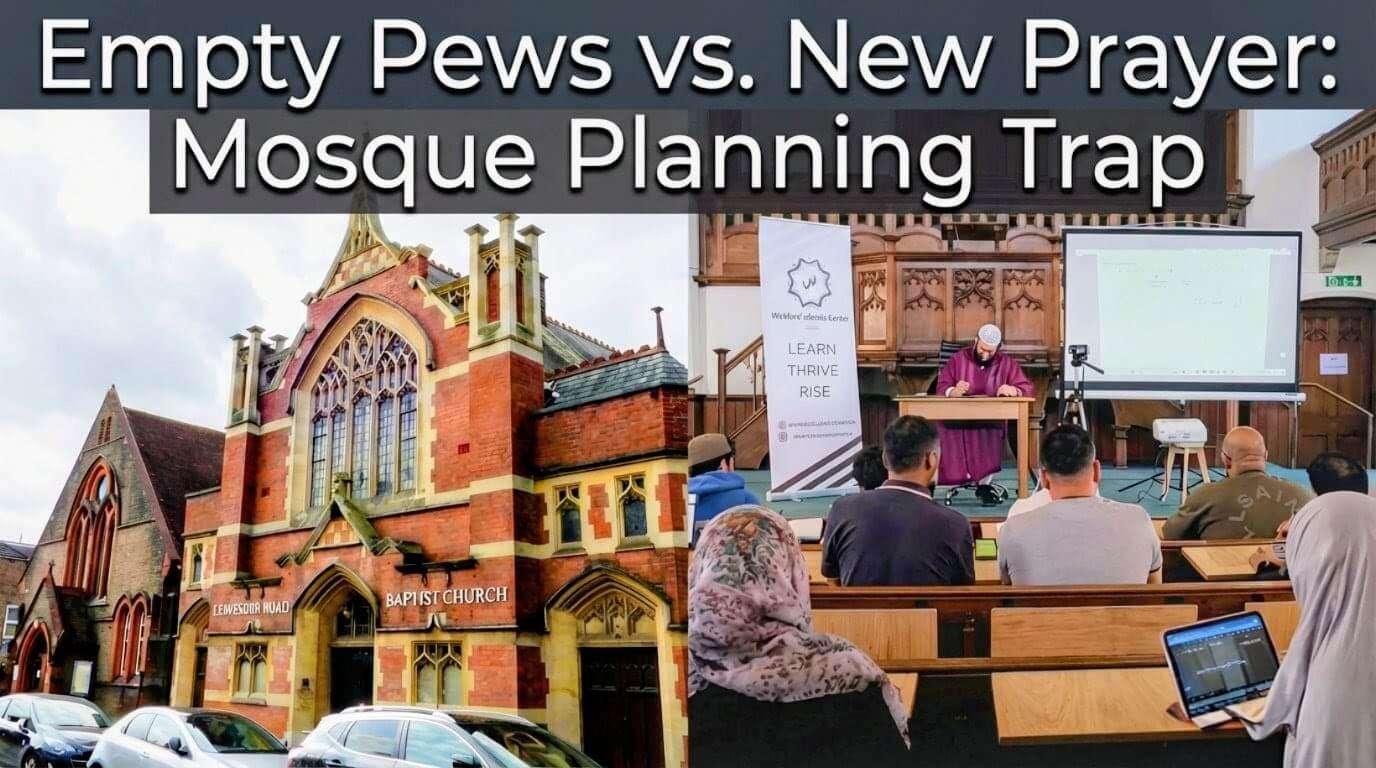

The Watford Stand-Off: A Case Study in Bureaucracy- In Watford, the recent rejection of the Leavesden Road Baptist Church proposal serves as a prime case study for this national trend. The building, which has sat largely vacant since 2021, was the subject of an ambitious bid by local entrepreneur Shabaz Khaliq to establish a mosque, nursery, and community hub. Despite the applicant already hosting youth clubs and literacy programs on-site, the council officially blocked the permanent change of use in late 2025.

The refusal focused heavily on the "excessive" nature of internal modifications required to accommodate Islamic prayer, such as the removal of fixed pews. This creates a "heritage trap" where a building is deemed too precious to change but too expensive to maintain, often leading to years of dereliction. Just miles away, the St Thomas' United Reform Church—vacant since 2015—faces a similar fate, with a final decision on its conversion into Masjid Al-Ummah pending for February 3, 2026.

Appeal Data: The Steep Climb to Overturn Rejections- Exclusive data analysis for 2025 reveals that the path to overturning these rejections is increasingly narrow. The Planning Inspectorate's latest statistics show that the success rate for general planning appeals (Section 78) currently sits at approximately 30%. However, for "Change of Use" applications involving religious institutions—which are often more complex and controversial—the success rate via written representations is significantly lower, at roughly 18-20%.

While the High Court and the Supreme Court have recently upheld the power of local authorities to regulate their proceedings and restrict voting on sensitive planning applications, they have also clarified that "light touch" prior approvals must still strictly consider heritage impacts. This legal landscape means that even when a community group appeals a council’s rejection, the odds of a reversal are less than one in five unless the case proceeds to a full public inquiry. Interestingly, inquiries have a much higher success rate of nearly 60-75%, but the legal costs—often exceeding £50,000—place this route out of reach for most local Muslim charities.

The Main Drivers of Rejection and the Heritage Trap- The primary reasons for blocking these applications generally fall into three categories. First is "Heritage Impact," where the requirement for open prayer space is deemed incompatible with historic church interiors. Second is "Parking and Amenity," with councils often applying peak-hour traffic logic to prayer times that do not align with standard rush hours. Third is the "Public Benefit" test; under the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), applicants must prove that the community benefit outweighs the "substantial harm" to a heritage site.

The irony of these planning battles is the economic and social cost of vacancy. Many of these properties have been empty for over a decade, becoming magnets for anti-social behavior. The Ar-Rahmah Trust, for example, purchased the St Thomas' site for £3.5 million with plans for a £500,000 renovation. When such private investments are blocked, the burden of maintaining the deteriorating asset often falls back onto the local taxpayer or leads to the eventual total loss of the building's historical value.

.svg)