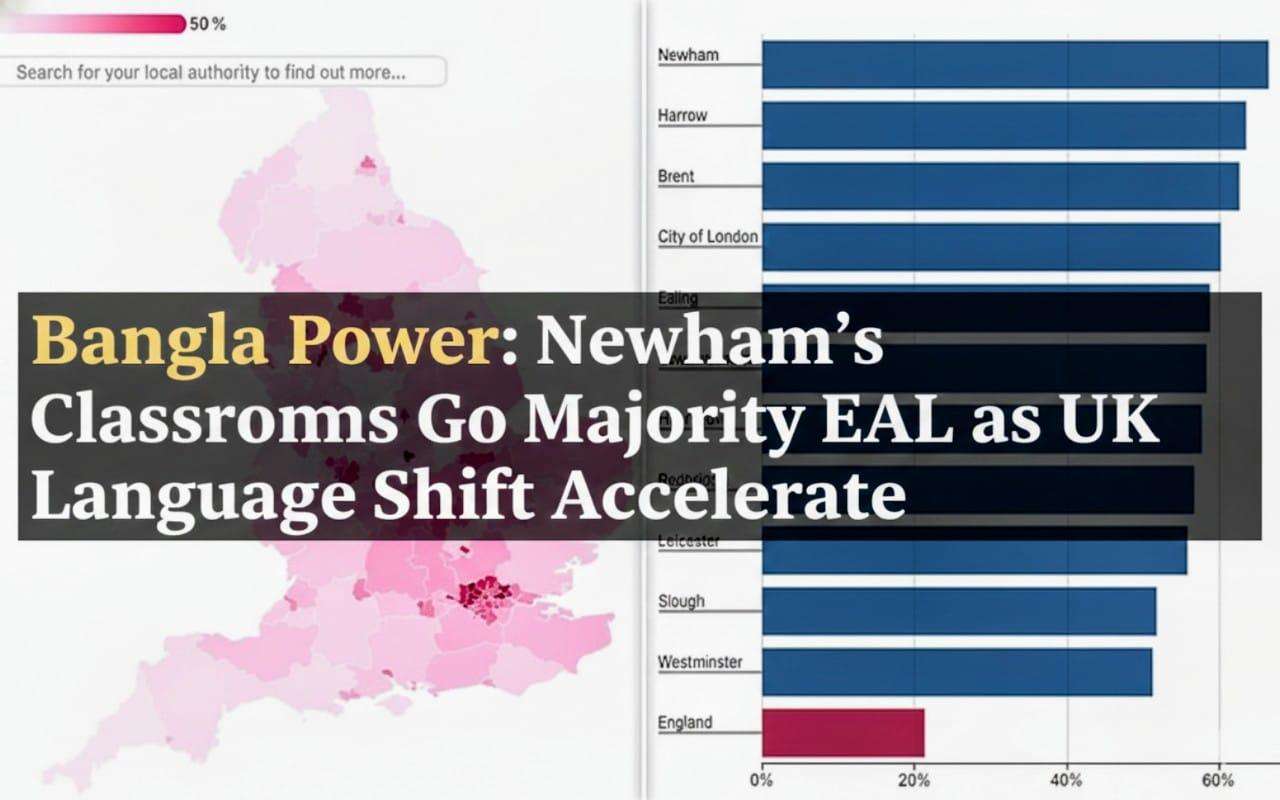

A profound and ongoing linguistic transformation is reshaping the fabric of England's schools, presenting both unique challenges and opportunities for the education system. Recent analysis of Department for Education (DoE) data reveals that English is no longer the first language for the majority of pupils in 11 of England's 153 local educational authorities, representing roughly one in every 15 councils. This dramatic shift highlights the rapid change driven by demographic shifts, with the nationwide figure now standing at approximately 1.8 million pupils, or one in five, for whom English is an Additional Language (EAL)—a substantial increase from 1.1 million just a decade ago.

The Epicentre of Linguistic Change

The most pronounced concentration of this diversity is found in London boroughs. Newham, in East London, records the highest rate, where a striking 66% of pupils do not have English as their mother tongue. Close behind are Harrow and Brent, both registering similarly high rates of 63%. Beyond the capital, the overall trend is clear, with languages such as Urdu, Polish, and Panjabi now featuring prominently in classrooms across the country.

A key language contributing to this diversity, particularly in London, is Bengali (Bangla). While the primary EAL languages mentioned in the initial data frequently include Urdu, Polish, and Panjabi, evidence confirms that Bengali holds a significant position. The 2021 Census for England and Wales ranked Bengali as the eighth most spoken language overall, with 199,000 speakers. More specifically, it is officially the second most spoken primary language in London after English, with approximately 71,609 residents using it as their main language at home, particularly concentrated in East London.

The British Bangladeshi Community Footprint

The prevalence of Bengali language speakers is directly tied to the established and growing British Bangladeshi community. The 2021 Census estimates the total British Bangladeshi population in England and Wales at 644,881 people, constituting 1.1% of the total population. This group is highly concentrated geographically. For example, the London borough of Tower Hamlets has, by far, the largest proportion of Bangladeshi residents in the UK, where they make up nearly 35% of the population. Newham, also an area of high EAL rates, has a Bangladeshi population share of 15.9%. This concentration explains the high number of Bengali-speaking pupils in East London schools.

Significantly, studies have indicated that pupils from Bangladeshi heritage can demonstrate high academic achievement. Research has shown that cohorts of Bengali speakers were achieving results above the national average in primary schools, with some studies suggesting EAL pupils, including those of Bangladeshi heritage, can even outperform native English speakers at certain key stages. For instance, in Tower Hamlets, pupils of Bangladeshi heritage have been noted to attain better results than the London average, turning linguistic diversity into a proven educational strength for many.

Financial and Societal Stress Points

This rapid increase in linguistic diversity places considerable strain on school resources and budgets. Schools are compelled to divert limited funds to provide essential EAL support, which includes translated versions of educational materials, adding subtitling and voiceovers, and funding in-class interpreters. This vital support, while necessary for integration and success, pulls resources away from mainstream teaching provisions.

Critics from groups like Migration Watch UK argue that English is the essential 'glue' for societal cohesion, raising concerns that this rapid multilingualism places integration at a "serious risk." They point to the pace of change, suggesting that English could become a minority home language nationwide within the next few decades if current trends continue. Conversely, supporters of multilingualism highlight the social and cognitive benefits, citing studies that show EAL students' presence has no negative impact on the learning of other pupils.

Ultimately, the figures underscore a fundamental shift in the UK's educational and social landscape. While the country's diverse linguistic makeup is an expression of its multicultural character, the government and local authorities face a complex challenge: ensuring that schools are properly funded and equipped to support the needs of all pupils, fostering both linguistic integration and academic success across all communities, from the high concentrations of Bengali speakers in Tower Hamlets and Newham to the more varied EAL populations elsewhere.

.svg)